« February 2005 | Main | April 2005 »

March 27, 2005

Get smart for just $9.99

CONSUMER COGNITION AND PRICING IN THE 9’S IN OLIGOPOLISTIC MARKETS.

Marketing research has confirmed what many know, that a large number of goods are priced to the end in a 9, for example hamburgers for 99 cents or shoes for 49 dollars, what is referred to as odd-pricing or psychological pricing. With a look at a spreadsheet analysis of both wholesale and retail prices, you will see that wholesale prices (when looking at the last two right digits) are distributed very evenly over the range of 00 to 99, but when you look at retail pricing you see the obvious, that many prices end with 09, 19, ... , 99.

Do consumers do this out of irrationality or only when they expect the time cost of fully calculating the exact price to exceed the expected loss caused by the slightly erroneous but higher price paid by failing to accurately incorporate the rightmost digits? What kind of effect does pricing in the 9’s have on a market where there may be some non-strict equilibrium found where even or non-9 price ending occurs? A recent article out of The Harvard Institute for Economic Research (HIER) investigates what effect this phenomena may have on oligopolistic markets and attempts to build a model of the kinds of markets we may expect to result from pricing in the 9’s.

ABSTRACT:

"The paper fully characterizes the Bertrand equilibria of oligopolistic markets where consumers may ignore the last (i.e. the right-most) digits of prices. Consumers, in this model, do not do this reflexively or out of irrationality, but only when they expect the time cost of acquiring full cognizance of the exact price to exceed the expected loss caused by the slightly erroneous amounts that is likely to be purchased or the slightly higher price that may be paid by virtue of ignoring the information concerning the last digits of prices. It is shown that in this setting there will always exist firms that set prices that end in nine though there may also be some (non-strict) equilibria where a non-nine price ending occurs. It is shown that all firms earn positive profits even in Bertrand equilibria. The model helps us understand in what kinds of markets we are most likely to encounter pricing in the 9's."

QUOTES:

"Given the limits of the human brain, it is reasonable to assume human beings will not be fully informed. When a person goes through a supermarket buying goods, is it worthwhile for him to study and take in the price information of each product in full? It is not evident that the answer to this will be yes, contrary to what early textbook models of economics suggested. Indeed it may not be rational to take in so much information.5 If, for instance, he looked only at the dollar part of the prices and took his purchase decisions based on that, he would make a few wrong decisions, true, but the time saved by using this strategy may be well worth that little loss. I shall later model the circumstances where such time-saving is worthwhile."

"The model predicts that prices will generally end in 9s but in some markets there will be two modal price endings, one of which will invariably be 9. It is interesting to note that the asymmetric equilibrium in which the non-9 ending occurs would exist only if the indifference axiom holds. It is arguable that for products where people buy large amounts of some commodity or agree to a per unit price and then buy the commodity or service over a long period of time the indifference axiom is less likely to be satisfied. In such cases a small price difference translates into a large loss or gain for the buyer and hence consumers are more likely to take cognizance of the exact price. Hence for these kinds of goods multiple prices are less likely to occur in the same market."

"There is a large literature in psychology that illustrates how human beings often use simple rules of thumb to make decisions, instead of collecting all relevant information and then making decisions; and how these "fast and frugal" rules may in fact turn out to be reasonable (Gigerenzer and Goldstein, 1996; Gigerenzer and Selten, 2001). If for instance, people were given pairs of cities and asked which of each pair had the higher population and people named the city they were more familiar with*, Goldstein and Gigerenzer (1999) showed that they would be right significantly more often than if they chose the answer at random. Given that the collection of information can be costly in terms of time and money, for certain purposes the use of this heuristic may be the rational course. It is this general idea that I shall now use in the context of consumer decision-making concerning what to buy."

* It would be more correct to say "the city they recognized" - Ed.

"Unlike in the model of monopoly discussed in Basu (1997), we find that firms benefit from this phenomenon of pricing in the nines. This enables (sophisticated) Bertrand oligopolists to sustain a price above the marginal cost (and even above the prices that could prevail in the standard Bertrand oligopoly model with an exogenously fixed smallest unit of change). Also, unlike in a monopoly, some non-9 endings are now possible in equilibrium."

"Another natural way to extend the model is to suppose that, if a person is planning a very large purchase, he takes cognizance of the exact per-unit price of the product since even a tiny difference in per-unit price could make a big difference to his cost. While I have not modeled this formally here, it is reasonable to expect that in such situations the indifference axiom discussed above will be violated and so we will invariably see only one price for each good. If we go a step further and introduce the idea of 'cautious behavior' on the part of consumers, which is defined behavior that takes into account the possibility of 'trembles' in prices whether or not there exists any actual price variability in the market, then it is likely that the dominance of 9 endings will break down. For goods, where the consumer places large orders (that is, several multiples of the unit) on the basis of a per-unit price, there will be a unique price but there will be no special reason for this to have a 9-ending. Hence, for goods like cement, house paint, phone calls and long-term lawn-mowing contracts we will be less likely to see nine price endings. By the same kind of reasoning we would expect to see a wider use of prices ending in 9 in the retail market, where small quantities of goods are purchased, or in the market for perishable goods, as opposed to, for instance, the wholesale market."

"...instead of assuming consumer irrationality and consumer psychological delusion, if we simply recognized that consumers have limited time for decision-making and limited brain capacity and they act rationally subject to these limitations, then we can get results which elude the standard literature on industrial pricing and mimic some of the results which behavioral economics derives only by assuming consumer irrationality. This is not to suggest that consumers are never irrational but simply that we must not be too hasty in jumping to the conclusion of irrationality either."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Kaushik Basu

Kaushik Basu is a Professor of Economics and the Carl Marks Professor of International Studies at The Department of Economics, Cornell University. He received his PhD from The London School of Economics in 1976. His expertise includes Economic development, economic theory, industrial organization and political economy. His research interests include economic development, economic theory, industrial organization, and political economy. He has held visiting positions at CORE (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium), the Institute for Advanced Study (Princeton), and the London School of Economics, where he was a Distinguished Visitor in 1993. He also has been a Visiting Professor at Harvard University and Princeton University.

Kaushik Basu Homepage at Cornell University

Posted by DSN at 09:34 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

March 23, 2005

EACR 2005

THE 2005 EUROPEAN ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH (EACR) CONFERENCE

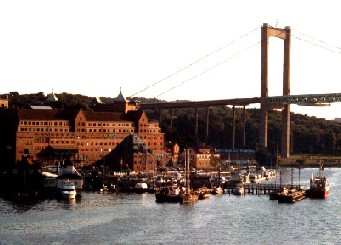

The seventh European ACR will take place June 15-18 in the second largest city in Sweden, Göteborg. The aim of the conference is to contribute to the development of consumption research by including a wide range of phenomena, perspectives and disciplines.

"We hope to create a conference together that will be rich in rewards both professionally and socially. We hope the conference will strengthen the ties between researchers who work within the field of consumption. We want to set the scene for a conference that makes use of the full potential of in-depth specialization as well as interdisciplinary cooperation. It is our hope that presentations and discussions will enhance our knowledge of consumption. Göteborg is the second largest city in Sweden located between the sea and the forest. We are sure that the weather will be at its best with long light evenings. You will be able to enjoy stimulating conversations with old friends and new acquaintances."

From the EACR Homepage

The EACR welcomes researchers and doctoral students from universities all over the world. Registration is now open. Click here for more information.

The EACR 2005 Program Committee consists of:

*Eric Arnould, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA

*Russell W. Belk, University of Utah, USA

*Janet Borgerson, University of Exeter, United Kingdom

*Richard Elliot, Warwick Business School, The University of Warwick, United Kingdom

*Asim Fuat Firat, University of Southern Denmark- Odense, Denmark

*Jim Gentry, University of Nebraska- Lincoln, USA

*Margaret Hogg, Lancaster University, United Kingdom

*Robert Kozinets, Kellogg School of Management, USA

*Pauline Maclaran, De Montfort University, USA

*Lisa Penaloza, University of Colorado, USA

*Linda Price, University of Nebraska- Lincoln, USA

*Michael Saren University of Leicester, United Kingdom

*Alladi Venkatesh, University of California, USA & Stockholm School of Economics, Sweden

Doctoral Symposium:

Jonathan Schroeder – University of Exeter, United Kingdom

Posted by DSN at 10:44 AM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

March 21, 2005

Research position deluxe

RESEARCHER POST WITH LAIBSON AT HARVARD

Laibson's one of the smartest folks around and the salary is good even by postdoc standards.

"Professor David Laibson (Harvard University and the National Bureau of Economic Research) seeks an outstanding economics researcher who is willing to commit to work for two years as a full-time research assistant on a range of behavioral economics research projects, including half-time work on a textbook with a behavioral economics orientation. Annual compensation will be approximately $50,000. See here for examples of the kinds of research that will be undertaken. Applicants should have very strong grades, research experience, and training in statistics/econometrics. Interested individuals should immediately send an electronic course transcript, resume, cover letter, and writing sample to beshears at fas dot harvard dot edu."

Posted by dggoldst at 02:02 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

March 20, 2005

How to improve university education

IMPROVING LEARNING AT UNIVERSITIES: WHO IS RESPONSIBLE?

Last Fall, Wharton Marketing professor J. Scott Armstrong wrote a letter to the Wall Street Journal about the failure of business schools to teach students to do such fundamental things as give effective oral presentations, write persuasive management reports, listen to others, conduct meetings, and use statistical procedures to analyze data. This letter generated responses from "alumni, faculty, recruiters, consultants and students," spurring Armstrong to write a practical piece in the University of Pennsylvania Almanac Improving Learning at Universities: Who is Responsible?.

Armstrong argues the problem is not just based upon perception. Research has documented the failure of formal education to enable students to become more effective on the job or in other areas of their life. According to Armstrong, we have designed a system that convinces the majority of students that they are not responsible for their own learning. Possible causes of this misplaced responsibility are suggested. Armstrong concludes by proposing actions schools and universities can take.

QUOTE:

"Why is the educational system ineffective in teaching people to apply their knowledge? It is that we have designed a system that convinces most students that they are not responsible for their own learning. Surprisingly, the problem starts as soon as people are placed in groups. Zajonc’s (1965) review of social facilitation research, done on rats and students, found that when subjects observe the critical responses of others, their learning is inhibited. This led Zajonc to conclude, "students should study alone," (He did not provide advice for rats). The presence of a teacher compounds the problem (Browne et. al. 1991; Tough 1982). Grading saps responsibility and thus inhibits learning (Condry 1977; Levine and Fasnacht 1974). Student evaluations of teachers lead to a further erosion of their responsibility because the students place the responsibility on the professor (Armstrong 1998; 2004b), not to mention that the evaluation process is viewed by some as a demoralizing and demeaning exercise for faculty (Gray & Bergmann 2003)."

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

J. Scott Armstrong is Professor of Marketing at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. His research interests include forecasting methods; strategic planning; survey research; research methods, scientific communication; educational methods; social responsibility in management; persuasion through advertising. He received his PhD in Management; Marketing (with work in applied statistics, social psychology, and economics); Ford Foundation Fellowship, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1968.

Selected Recent Publications

* Principles of Forecasting: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001. Contributions from 40 authors, as well as the Forecasting Dictionary.

* Long-Range Forecasting: From Crystal Ball to Computer New York: Wiley Interscience, 1978; 7 printings of 1st Edition; 2nd Edition published 1985 (700 pages). The most frequently cited book on forecasting methods.

Posted by DSN at 07:06 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

March 17, 2005

To plan or not to plan?

DOES FORMAL STRATEGIC PLANNING REALLY HELP?

J. Scott Armstrong released to the world this worthwhile essay today:

"Some experts recommend that firms should adopt a flexible (informal) approach to developing marketing strategy. Formal planning, they say, can be a straightjacket that harms performance, especially when there is much uncertainty and change. Research has shown this to be incorrect.

Not all approaches to formal planning are useful.

Consider Porter's Five Forces, experience curves, mission statements, focus groups, SWOT, scenarios, and portfolio matrix methods like BCG. These methods are popular. Using Google, I searched for these terms plus the word "planning" and found from 940 sites for experience curves, to 2,330,000 for scenarios. However, I am unaware of any evidence that these procedures lead to better planning. On the contrary, there is evidence that some of these procedures are harmful to performance.

Some formal planning procedures do work.

To identify effective formal planning procedures, I reviewed research on corporate planning. This led to the development of a five-step formal planning process with explicit (written) procedures for:

1) determining the firm's long-range objectives,

2) generating alternative strategies,

3) evaluating alternative strategies,

4) monitoring implementation and outcomes, and

5) gaining commitment from those who will be affected by the plan.

Laboratory studies with small groups show that use of each of these steps improves group performance.

But does this five-step process help in large organizations? To address this, I searched for comparative empirical research on corporate planning procedures in firms and other organizations. Some of these studies looked at performance (e.g., profits) after formal planning procedures were introduced. Some compared organizations that used these procedures with those that did not. Also, in an experimental study, organizations received funds for planning, but for half the organizations the funds were contingent on following the five-step planning process.

Overall, formal planning was more profitable in 20 studies (including the experimental study), and harmful in only 3 (there were 5 ties). What is remarkable about these results is that with the exception of the experimental study, none of the organizations followed all aspects of the formal planning process. In many cases, one might judge the implementation of the process as poor. And, of course, there were often factors other than the planning process that might affect performance.

Since completion of my reviews, I have become aware of 14 recent studies, and formal planning was superior in 13 of them. Thus, despite problems with implementation and assessment, formal planning was associated with better performance in nearly 80% of the 42 studies and poorer performance in fewer than 8% of them.

Formal planning works under some conditions.

These results are also remarkable because, judging from the research, formal planning is only expected to be useful for situations involving:

* Large changes, such as for mergers, or when new products are introduced, or when a firm makes major changes in its marketing,

* High uncertainty, such as when facing changes in the economy or changes in government regulations,

* High complexity, where different parts of an organization need to work together, or

* Inefficient markets, where prices do not provide signals.

Because these conditions are common, however, many organizations could use some or all of the five-step process to improve performance.

Few, if any, organizations use this five-step procedure for planning.

Descriptive studies of planning show that few organizations use aspects of this five-step procedure. I have never encountered an organization that uses all steps, so I would appreciate hearing about such organizations.

[The above findings have been described in a series of papers available in full text under "Strategy and Planning" at http://jscottarmstrong.com. Additional studies are summarized in George Boyne's "Planning, Performance and Public Services," Public Administration, 79 (2001), 73-88.]"

Posted by dggoldst at 10:34 AM | Comments (0)

March 15, 2005

Worried about AMA interviews?

EVERYTHING YOU EVER WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT THE AMA INTERVIEWS FOR THE ACADEMIC MARKETING JOB MARKET

by Dan Goldstein March 2005

WHY AM I WRITING THIS?

I’ve seen the Marketing job market turn happy grad students into quivering masses of fear. I want to share my experiences and provide a bit advice to make the whole process less mysterious.

WHAT DO I KNOW?

I’ve been on the AMA job market twice and the Psychology market once. I’ve had about 40 AMA interviews, as well as numerous campus visits, face-to-face interviews, offers, and rejections. I’m an outsider to Marketing who went on the market older and with more experience than the average rookie (35 years of age, with 8 years of research scientist, postdoc, visiting scholar, and industry positions). I’ve hired many people for many academic posts, so I know both sides.

HOW TO SET UP AMA INTERVIEWS

First, at least a couple months before the conference, find where it will be. It's called the Summer Educator’s Conference. Strange name, I know. Got a room at the conference hotel, preferably on the floor where the express elevator meets the local elevator for the upper floors. You'll be hanging out on this floor waiting to change elevators anyway, so you might as well start there.

Next, get your advisor / sponsor to write a cover letter encouraging people to meet with you at AMA. It helps if this person is in Marketing. Get 1 or 2 other letters of recommendation, a CV, and some choice pubs. Put them in an envelope and mail them out to a friend of your sponsor at the desired school. It should look like the letter is coming from your sponsor, even though you are doing the actual assembly and mailing. Repeat this process a bunch of times. It's a good idea to hit a school with 2 packets, 3 if you suspect they're a little disorganized. Certainly send one to the recruiting coordinator (they may send letters to your department's secretary telling you they are hiring) and one to your sponsor's friend. Mail to schools regardless of whether they are advertising a position or not. This is academia: nobody knows anything. This means you may be sending 50 or more packets.

THEN WHAT?

Wait to get calls or emails from schools wishing to set up AMA interviews with you. These calls may come in as late as one week before the conference. Some schools will not invite you for totally unknown reasons. You may get interviews from the top 10 schools and rejected from the 30th-ranked one. Don't sweat it. Again, this is a land of total and absolute nonsense that you're entering into. Also, know that just because you get an interview doesn't mean they have a job. Sometimes schools don't know until the last minute if they’ll have funding for a post. Still, you'll want to meet with them anyway. After the AMA, you'll hopefully get "fly-outs," that is, offers to come and visit the campus and give a talk. This means you've made the top five or so. Most offers go down in December, but sometimes later. There's a second market that happens after all the schools realize they've made offers to the same person. Of course, some schools get wise to this and don't make offers to amazing people who would have come. We need some kind of point market to work out this part of the system perhaps.

THE "IT'S ALL ABOUT FRIENDSHIP" RULE

Keep in mind that you will leave this process with 1 or 0 jobs. Therefore, when talking to a person, the most likely thing is that they will not be your colleague in the future. Therefore, you'd better work hard to make them your friend. You'll need friends to collaborate, to get tenure, get grants, and to go on the market again if you’re not happy with what you get.

HOW DO THE ACTUAL AMA INTERVIEWS GO?

At the pre-arranged time you will knock on the hotel room door. You will be let into a suite (p=.4) or a normal hotel room (p=.5, but see below). In the latter case, there will be people you once imagined as dignified sitting on beds. The other people in the room may not look at you when you walk in because they will be looking for a precious few seconds at your CV.

THE SEAT OF HONOR

There will be an armchair. Someone will motion towards the armchair, smile, and say, "You get the seat of honor!" This will happen at every school, every time, for three days. I promise.

THE TIME COURSE

There will be two minutes of pleasant chit-chat. They will propose that you talk first and they talk next. There will be a little table next to the chair on which you will put your flip book of slides. You will present for 30 minutes, taking their questions as they come. They will be very nice. When done, they will ask you if you have anything to ask them. You of course do not. You hate this question. You make something up. Don't worry, they too have a spiel, and all you need to do is find a way to get them started on it. By the time they are done, it's time for you to leave. The whole experience will feel like it went rather well.

PREDICTING IF YOU WILL GET A FLY-OUT

It's impossible to tell from how it seems to have gone whether they will give you a fly-out or not. Again, this is total and absolute madness. They might not invite you because you were too bad (and they don't want you), or because you were too good (and they think they don't stand a chance of getting you).

DO INTERVIEWS DEVIATE FROM THAT MODEL?

Yes.

Sometimes instead of a hotel room, they will have a private meeting room (p=.075). Sometimes they will have a private meeting room with fruit, coffee, and bottled water (p=.025). Sometimes, they will fall asleep while you are speaking (p=.05). Sometimes they will be rude to you (p=.025). Sometimes, if it's the end of the day, they will drink alcohol with you (p=.18, given that it's the end of the day).

HOW YOU THINK THE PROCESS WORKS

The committee has read your CV and cover letter and looked at your pubs. They know your topic and can instantly appreciate that what you are doing is important. They know the value of each journal you have published in and each prize you’ve won. They know your advisor and the strengths she or he instills into each student. They ignore what they’re supposed to ignore and assume everything they’re supposed to assume. They’ll discount the interview and fly you out based on your record.

HOW THE PROCESS REALLY WORKS

The interviewers will have looked at your CV for about one minute a couple months ago, and for a few seconds as you walked in the room. They will never have read your entire cover letter, and they will have forgotten most of what they did read. They could care less about your advisor and will get offended that you didn't cite their advisor. They'll pay attention to everything they're supposed to ignore and assume nothing except what you repeat five times. Flouting 50 years of research in judgment and decision-making, they’ll discount your CV and fly you out based on your interview.

TWO WAYS TO GIVE YOUR SPIEL

1) The plow. You start and the first slide and go through them until the last slide. Stop when interrupted and get back on track.

2) The volley. Keep the slides closed and just talk with the people about your topic. Get them to converse with you, to ask you questions, to ask for clarifications. When you need to show them something, open up the presentation and show them just that slide.

I did the plow the first year and the volley the second year. I got four times more fly-outs the second year. Econometricians are now trying to determine if there was causality.

HOW TO ACT

Make no mistake, you are an actor auditioning for a part. You have to be like Santa Claus bringing the energy into the room with you. There will be none awaiting your arrival, I promise you. These people are tired. They’ve been listening to people in a stuffy hotel room from dawn till dusk for days. If you do an average job, you lose: You have to be two standard deviations above the mean to get a fly-out. So audition for the part, and make yourself stand out. If you want to learn how actors audition, read Audition by Michael Shurtleff.

HAVE A QUIRK

One of the biggest risks facing you is that you will be forgotten. Make sure the interviewers know something unusual about you. My quirk is that I've worked all over the world as a theater director for over 10 years. It's got nothing to do my research, but I can't tell you the number of people who bring up this odd little fact when I do campus visits.

DON'T GIVE UP

Never think it's hopeless. Just because you're not two SDs above the mean at the school of your dreams, doesn't mean you're not the dream candidate of another perfectly good school. The students are competing for schools and the schools are competing for students. If you strike out, you can just try again next year. I know a person in Psychology who got 70 rejections in one year. I know a person in Marketing who was told he didn't place in the top 60 candidates at the 20th ranked school. The subsequent year, both people got hired by top 5 departments. One of them is ridiculously famous!

RUMORS

Don't gossip. All gossip can mess with your chances. Gossip that you are doing well can hurt you because schools will be afraid to invite you if they think you won’t come. Gossip that you are doing poorly can hurt you because schools that like you will be afraid to invite you if they think no one else does. Sometimes people will ask a prof at your school if you would come to their school, and the prof will then ask you. To heck with that. Just say that if they want to talk to you, they should deal with you directly.

The danger of rumors can be summed up by the following story. At ACR in 2003, I was having a beer with someone who confessed, "you know, my friend X at school Y told me that they want to hire you, but they're afraid your wife won't move to Z". I was single.

ADDENDUM

Have your own advice to add? Want more detail on specific parts of the process? Let me know. dan at dangoldstein dot com.

Posted by dggoldst at 07:47 PM | Comments (0) | TrackBack

March 14, 2005

Trust has a substitute?

TRUST BUT VERIFY: MONITORING IN INTERDEPENDENT RELATIONSHIPS

Effective organizations depend upon employees who will rely upon each other even when they do not trust each other. How then can managers promote trustworthy behavior to maintain the effectiveness of their organizations? Managers, employees, and customers routinely rely upon others to choose trustworthy actions. Managers trust that employees will complete work, employees expect that they will be paid, and customers expect goods and services to be delivered on time. Trust reduces transaction costs, improves efficiency of economic transactions, and enables managers to negotiate more efficiently and lead more effectively. A trusting environment, though, is not necessarily the norm. In many organizational settings, including negotiations and accounting, people routinely engage in untrustworthy and unethical behavior. The effect of this kind of behavior on trust has been demonstrated in numerous studies, which identify various individual and contextual factors that influence trust. One such study employing repeated prisoner’s dilemma and ultimatum games found that responders were more likely to reject offers proposed by those that had previously used deception in the past. What then can a manager do when trust is low? Monitoring is one approach. For example, some managers randomly administer drug tests, conduct audits and even listen in on phone calls. Between 1990 and 1992 over 70,000 US companies purchased surveillance software at a cost of more than $500 million (Aiello, 1993). Although popular, what are the relationships between different monitoring systems and the actions people choose? A recent article by Maurice E. Schweitzer and Teck H. Ho examines the dynamics of monitoring. They find that frequent monitoring generally increases trust-like behavior. When monitoring is anticipated, trust-like behavior is increased: monitoring is a substitute for trust. However, the study finds that people are particularly untrustworthy when monitoring is unanticipated. In short, monitoring is difficult to turn off once initiated.

ABSTRACT:

"For organizations to be effective, their employees need to rely upon each other even when they do not trust each other. One tool managers can use to promote trust-like behavior is monitoring. In this article we report results from a laboratory study that describes the relationship between monitoring and trust behavior. We randomly and anonymously paired participants (n=210) with the same partner, and had them make 15 rounds of trust game decisions. We find predictable main effects (e.g., frequent monitoring increases trust behavior) as well as interesting strategic behavior. Specifically, we find that anticipated monitoring schemes (i.e., when participants know before they make a decision that they either will or will not be monitored) significantly increase trust behavior in monitored rounds, but decrease trust behavior overall. Participants in our study also reacted to information they learned about their counterpart differently as a function of whether or not monitoring was anticipated. Participants were less trusting when they observed trustworthy behavior in an anticipated monitoring period than when they observed trustworthy behavior in an unanticipated monitoring period. In many cases, participants in our study systematically anticipated their counterpart’s untrustworthy behavior. We discuss implication of these results for models of trust and offer managerial prescriptions."

QUOTES:

"While prior work has argued that trust is an essential ingredient for managerial effectiveness (Atwater, 1988), many relationships within organizations lack trust. For example, managers within large organizations with high turnover may not have sufficient time to develop trust among all of their employees. Even in the absence of actual trust, however, managers need to induce trust-like behavior. In this article we conceptualize monitoring as a substitute for trust, and we demonstrate that monitoring systems significantly influence trust-like behavior."

"We conceptualize monitoring as a tool to produce trust-like behavior, and we consider ways in which monitoring changes incentives for engaging in trust behavior. We adopt a functional view of trust by assuming individuals calculate the costs and benefits of engaging in trust behavior in a manner consistent with Ajzen’s (1985, 1987) theory of planned behavior. In particular, we focus on the role of monitoring systems in altering the expected costs and benefits of choosing trust-like actions. This conceptualization matches our experimental design, because participants in our study are paid for their outcomes and remain anonymous to their counterpart. There is no way for participants to find out who their partners are, and as a result, participants in our study face a well-defined "shadow of the future" defined by the future rounds of a repeated trust game."

"Consider monitoring regimes that range from one extreme, complete monitoring, to another extreme, no monitoring. Under complete monitoring, participants have an incentive to exhibit trust-like behavior, especially in early rounds, because their counterpart will observe their actions and can reciprocate in future rounds. On the other hand, under no monitoring, participants have little incentive to engage in trust-like behavior, because their counterpart cannot observe their actions. In this case, the expected benefits of choosing untrustworthy actions exceed the expected benefits of choosing trust-like actions. If players are self-interested, opportunism is likely to prevail. The more frequent the monitoring, the greater the expected benefits of choosing trust-like actions. Consequently, we hypothesize that monitoring frequency will be positively correlated with trust-like behavior. With more frequent monitoring, untrustworthy behavior is more likely to be detected and subsequently punished or reciprocated. As a result, if players are calculative and maximize their total payoff for the entire interaction, they will exhibit more trust-like behavior when they experience more frequent monitoring."

"[A]nticipated monitoring schemes decrease trust- like behavior in periods of no monitoring by harming trust development. Players who observe others choosing trustworthy actions in anticipated monitoring periods may attribute the trustworthy behavior they observe to the monitoring scheme rather than the trustworthiness of the individual. As a result, players who observe trustworthy behavior in anticipated monitoring periods may be less likely to assume that their counterpart will choose trustworthy actions when they are not monitored. As a result, trustworthy actions are less diagnostic of true trustworthiness and less effective in building trust when the observed trust behavior occurs in an anticipated period of monitoring. For both of these reasons, we hypothesize that anticipated monitoring will decrease trust-like behavior in non-monitored rounds."

"First, we find that frequent monitoring increases overall trust-like behavior. Second, we find that anticipated monitoring harms overall trust-like behavior, but significantly increases trust-like behavior for periods in which monitoring is anticipated; in our study, Even players were particularly trustworthy in anticipated monitoring rounds, but were particularly untrustworthy when they anticipated no monitoring."

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Maurice E. Schweitzer

"

"Maurice E. Schweitzer is assistant Professor of Operations and Information Management at The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. He received his PhD the University of Pennsylvania in 1993. His research interests include deception and trust, negotiations and behavioral decision research. Currently he is working on projects involving the influence of emotions on trust, trust recovery, envy and unethical behavior and Insurance fraud.

Maurice E. Schweitzer Home Page at Wharton

Teck H. Ho

Teck H. Ho is the William Halford Jr. Family Professor of Marketing Executive Director at the Berkeley Experimental Social Sciences Laboratory (Xlab). He received his PhD from in Decision Sciences from The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania in 1993. His research interests current projects involve B2B contract design, Strategic IQ and trust building.

Teck H. Ho Homepage at The University of California at Berkeley.

Posted by DSN at 11:16 AM | Comments (0)

March 09, 2005

Honesty, No longer the best policy?

THE DIRT ON COMING CLEAN: PERVERSE EFFECTS OF DISCLOSING CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conflicts of interest have been at the heart of many business scandals. Investment bankers who get paid more when their clients trade more, or doctors who get paid more when their patients require more care, are both examples of advisors with a conflict of interest. The solution usually is considered to be a full disclosure of each party's conflict of interest. A recent article out of Carnegie Mellon University by Daylian Cain, Don Moore, George Loewenstein investigates to what extent the receivers of advice use this knowledge to counteract any given biases and how disclosure of conflicts affects the advice given. The authors argue such disclosure may not remedy conflicts but could possibly aggravate them.

ABSTRACT

"Conflicts of interest can lead experts to give biased advice. While disclosure has been proposed as a potential solution to this, we show that disclosure can have perverse effects, and might even increase bias. Disclosure may increase bias because advisors feel morally licensed and strategically encouraged to exaggerate their advice even further from the truth. As for those receiving the advice, proper use of the disclosure depends on understanding how the conflict of interest biased the advice and how that advice impacted them. Because people lack this understanding, disclosure can fail to solve the problems created by conflicts of interest."

QUOTES

"Perhaps, however, the benefits of disclosure should not be accepted quite so quickly. For disclosure to be effective, the recipient of advice must understand how the conflict of interest has influenced the advisor and must be able to correct for that biasing influence. In many important situations, however, this understanding and ability may be woefully lacking. For example, imagine a patient whose physician advises, "Your life is in danger unless you take medication X," but who also discloses, "The medication's manufacturer sponsors my research." Should the patient take the medication? If not, what other medication? How much should the patient be willing to pay to obtain a second opinion? How should the two opinions be weighed against each other? The typical patient may be hard-pressed to answer such questions."

"And what is the impact of disclosure on providers of advice? In the example just given, is it possible that the physician’s behavior might be affected by disclosure? For example, might the physician be more likely to exaggerate the danger of not taking the medication in order to neutralize the anticipated "warning" effect of the disclosure?"

"First, estimating the impact of a conflict of interest on an advice giver is an extraordinarily difficult problem that requires both economic and psychological insight. To properly estimate the degree to which a particular advisor is biased by a conflict of interest, one would want to know the extent to which the advisor embraces professional norms or is instead corrupt. One would also want to know how tempting the advisor finds the incentives for providing biased advice, and one would want to have an accurate mental model of how such incentives can bias advice. However, prior research suggests that most people have an incorrect understanding of the psychological mechanisms that transform conflicts of interest into biased advice."

"Research on what has been called the “failure of evidentiary discreditation” shows that when the evidence on which beliefs were revised is totally discredited, those beliefs do not revert to their original states but show a persistent effect of the discredited evidence (Skurnik, Moskowitz, and Johnson 2002; Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard 1975). Furthermore, attempts to willfully suppress undesired thoughts can lead to ironic rebound effects, in some cases even increasing the spontaneous use of undesired knowledge (Wegner 1994)."

"Disclosure, at least in the context of the admittedly stylized experiment discussed in this paper, benefited the providers of information but not its recipients. To the extent that a similar effect occurs outside the experimental laboratory, disclosure would supplement existing benefits already skewed toward information providers. In particular, disclosure can reduce legal liability and can often forestall more substantial institutional change. We do not believe that this is a general result—that is, that disclosure always benefits providers and hurts recipients of advice—but it should challenge the belief that disclosure is a reliable and effective remedy for the problems caused by conflicts of interest."

EXPERIMENTAL METHOD

"The estimation task involved estimating the values of jars of coins. Estimators were paid according to the accuracy of their estimates, and advisors were paid, depending on the experimental condition, on the basis of either how accurate or how high (relative to actual values) the estimators' estimates were.

In each round, advisors took turns at closely examining a jar of coins and then completed an advisor's report. Each advisor's report contained the advisor's suggestion of the value of the jar in question and provided a space in which the estimator would respond with an estimate of the jar's worth.

After seeing the reports, the estimators saw the jar in question -- but only from a distance of about 3 feet and only for about 10 seconds: the experimenter held the jar in front of estimators, turning the jar while walking along a line across the room and back. Estimators then attempted to estimate the value of the coins in the jar.

The amount of money in each of the six jars (M, N, P, R, S, and T) was determined somewhat arbitrarily to lie between $ 10 and $ 30, and advisors were informed of this range. Estimators were told that advisors had information about the range of actual values but were not given this range of values themselves. In fact, the values of the jars were M = $ 10.01, N = $ 19.83, P = $ 15.58, R = $ 27.06, S = $ 24.00, and T = $ 12.50. In the first three rounds, neither estimators nor advisors received feedback about their actual payoffs or about actual jar values. In each of the last three rounds, however, after advisors had given their advice and estimators had made their estimates, each advisor was shown the estimate of the estimator to whom their advice was given on the previous jar and, for each of the feedback rounds, the actual value of the jar in question was announced to everyone at the end of the round. Since payoff schedules were provided to all participants at the beginning of the experiment, feedback allowed both advisors and estimators to calculate how much money they had made in the previous round before continuing on to the next round. While estimators did not see the advisor's instructions, advisors saw a copy of the estimator's instructions and thus could also use feedback to calculate their estimator's payoffs.

Both estimators and advisors were paid on the basis of the estimator's estimates. Estimators were always paid on the basis of the accuracy of their own estimates. Advisors' remuneration depended on the condition to which they were assigned. In the "accurate" condition, each estimator was paid according to how accurate the estimator's estimate was, and this was disclosed prominently on the advisor's report immediately under the advisor's suggestion. ("Note: The advisor is paid based on how accurate the estimator is in estimating the worth of the jar of coins.") In the "high/undisclosed" and "high/disclosed" conditions, each advisor was paid on the basis of how high the estimator's estimate was. This conflict of interest was not disclosed in the high/undisclosed condition but was prominently disclosed in the high/disclosed condition, immediately under the advisor's suggestion. ("Note: The advisor is paid based on how high the estimator is in estimating the worth of the jar of coins.") In addition to being remunerated on the basis of their estimators' estimates, all advisors had an additional opportunity to earn money: after they had completed the report for each jar, advisors were asked to give their own personal best estimates of the true value of the coins in the jar and were rewarded on the basis of accuracy."

Advice provided for each jar, by condition

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Daylian Cain

"I am a 4th year doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business, (Pittsburgh, PA) where I concentrate on Organizational Behavior & Theory. My main area of interest is decision making -- both the normative aspects (as informed by Ethics and Economics) and the descriptive aspects (as informed by Social Psychology and Behavioral Decision Research). I also earned an academic background in Philosophy, where I was interested in theories of rationality and morality. These combined interests lead me to conduct research and lecture on topics such as managerial decision making, business ethics, and negotiations. "

Daylian Cain Home Page

Don Moore

Don Moore is an Assistant Professor in the Organzational Behavior and Theory group at the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon University. "The human mind, for all its miraculous power, does not come with an instruction manual. This ignorance has tremendous consequences, not only for the way we make decisions as individuals, but also for interactions (including negotiations), and for the organizations we create. My work seeks to fill important gaps in our understanding of ourselves and document the implications of these discoveries on social, organizational, and market outcomes."

Don Moore's Home Page

George Loewenstein

George Loewenstein is a professor in the Department of Social and Decision Sciences at Carnegie Mellon University. "My primary research focus is on intertemporal choice--decisions involving trade-offs between costs and benefits occurring at different points in time. Because most decisions have consequences that are distributed over time, the applications of intertemporal choice are numerous (e.g. saving behavior, consumer choice, labor supply).

In the past, formal analyses of intertemporal choice in economics and other social science disciplines have been dominated by a single model--the discounted utility model. I try to identify deficiencies with this model, explain these deficiencies in psychological terms and propose alternative models."

George Loewenstein Home Page

Posted by DSN at 09:29 PM | Comments (0)

March 01, 2005

Duncan Luce

DECISION SCIENCE RESEARCHER PROFILE: DUNCAN LUCE AWARDED 2003 NATIONAL MEDAL OF SCIENCE

R. Duncan Luce is a Distinguished Research Professor of Cognitive Science and Economics at UC Irvine. At the age of 79 Luce, in recognition of his work in the behavioral and social sciences, has been named one of eight U.S. scientists and engineers to receive the 2003 National Medal of Science; the highest scientific honor in the United States. On March 14, 2005 President George W. Bush will present them with the honor at the Whitehouse. Why it is awarded two years after 2003 is a mystery to us.

The National Medal of Science honors individuals both for pioneering and innovating scientific research that has led to a better understanding of the world, and for contributing to innovations and technologies that give the United States a global economic edge. The award was established in 1959 and is administered by the National Science Foundation.

Luce received his PhD in mathematics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1950. He feels there is an inherent link between math and psychology. "Given the fact that people manage to live together in a fairly reasonable way most of the time, there have to be behavioral regularities," he says. "Mathematical behavioral science attempts to formulate such regularities."

Professor Luce's contributions to mathematical psychology have had a great influence on how the field examines decision making and sensory psychology. Luce combines mathematical theory and experiments, in efforts to understand features of individual behavior and orientation to the world. His method includes the development of formal mathematical models that consequently contribute to the shaping of contemporary economics.

As a child, Duncan Luce liked painting pictures and was fascinated with airplanes. His parents swayed him against an artistic career and an astigmatism kept him from becoming a military pilot. But Luce has been flying high for years and continues to create new ideas in his field.- from Luce's homepage at UC Irvine.

Luce served as advisor to many successful graduate students, including Columbia University Center for the Decision Sciences Director, and past President of the Society for Judgment and Decision Making Elke Weber.

RESEARCH INTERESTS:

"The representational theory of measurement concerns the types of data that can be summarized in some numerical way. Much general theory has been developed (Foundations of Measurement, vols. 1,2,3, 1971, 1989, 1990, with D.M. Krantz, P Suppes, & A. Tversky) and still is being actively explored. Although some of my efforts lie in this general area, over the last seven years I have mostly been applying some of these ideas to individual decision making, where the numerical measures are called utility and subjective probability or weights. Recently I have been examining the kinds of behavioral laws that link riskless utility and risky utility. Accompanying the theoretical work is an empirical program in which these plausible behavioral properties are tested in computer-based, laboratory experiments. There are many tricky and interesting questions of how best to evaluate these properties. The results to date exhibit highly regular patterns that are nicely summarized by numerical models." -from Professor Luce's Homepage

RECENT BOOKS

(2000) Utility of Gains and Losses: Measurement-Theoretical and Experimental Approaches. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

(1997) Choice, Decision, and Measurement: Essays in Honor of R. Duncan Luce

(1993) Sound & Hearing: A Conceptual Introduction. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

(1991) Response Times: Their Role in Inferring Elementary Mental Organization: Oxford.

(1990) With D.H. Krantz, P. Suppes & A. Tversky. Foundations of Measurement, Vol. III, Academic Press.

Posted by DSN at 10:04 PM | Comments (0)